Programmers are always learning. Whether it's learning a new language, a new framework, design patterns, or even a keyboard shortcut. It makes them and their team more productive, saving valuable time for their company. But we rarely talk about the skill of making code easy to understand, about commenting and the enormous impact it can have on the productivity of a team. So let's put the art of commenting in the spotlight it deserves.

How important can commenting really be?

“Indeed, the ratio of time spent reading versus writing is well over 10 to 1. We are constantly reading old code as part of the effort to write new code. ...[Therefore,] making it easy to read makes it easier to write.” - Robert C. Martin

This quote really captures why more attention should go to writing comments. To write correct code, you first need to understand its context. To do so requires a lot of reading and in practice, you have to read a lot of code that you did not write yourself.

Sure, you save time by being knowledgeable in the language you have to write. But how much time can be saved in the future by making your code readable?

For those who are interested, here's a story on how one character and no comments cost our team four hours:

My team and I were working on a big new feature. This feature required a few new Spring microservices to be created. Each required similar auto-configuration to configure its database. The first microservice (called A) worked like a charm. It contained this (simplified) code fragment:

@Bean

@ConditionalOnClass(TargetDataSources.class)

public List<A> ABeans(TargetDataSources targetDatasources) {

targetDatasources.stream().map(d - > {

A a = A.create();

a.setChangeLog("classpath:a-changelog.yaml");

a.setDataSource(d);

a.setResourceLoader(applicationContext);

}).collect(Collectors.toList());

}

A colleague of mine was working in a different microservice B and wrote the following code fragment:

@Bean

@ConditionalOnClass(TargetDataSources.class)

public List<B> BBeans(TargetDataSources targetDataSources) {

targetDataSources.stream().map(ds - > {

B b = B.create();

b.setChangeLog("classpath:b-changelog.yaml");

b.setDataSource(ds);

b.setResourceLoader(applicationContext);

}).collect(Collectors.toList());

}

Looks pretty similar right? Well, it did not work. Can you guess why? My colleague looked at it for a while (say 30 minutes) and could not figure out the problem. He asked another colleague, who did not know it either. Then another. More time passed by, then I was invited into the call. They had done some more debugging and brainstorming and had remembered that I had worked on microservice A. Maybe I would have some useful insights.

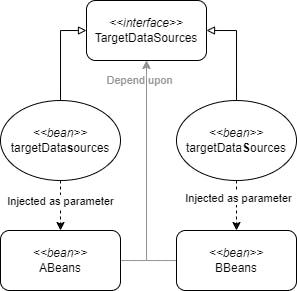

At first, I could not figure out the problem either. Then it hit me. The name of the parameter was the clue. See, the parameter of the example method was injected. As a team, we normally only dealt with dependency injection with one bean per interface. However, in these microservices, we used an extra library that introduced a second Bean of the type TargetDataSources. The library had foreseen this conflict and had 'cleverly' named their bean TargetDatasources. With a lowercase s! The other bean was named TargetDataSources. In both our microservices, we needed the bean with the lowercase s to be injected, which is why A was working and B was not.

No exception was occurring, because Spring was able to differentiate between the candidates based on the parameter name. To fix the bug, you had to know there were two candidates in the context and you had to know their case-sensitive names.

So what's the moral of this story? I should have added a comment pointing out the casing of the parameter and its importance. That one line of commenting would have saved hours of debugging. But when writing the fragment (months earlier) I had also spent hours figuring out I needed that casing. And once it finally worked, I was just relieved to move on and did not take a moment and think about future readers of this code fragment. An expensive mistake on my end.

What should I comment?

Okay, so commenting can be important. But then what should I comment? If you remember one thing from this article let it be to comment why rather than what. It's the biggest timesaver you can give to the future reader of a code fragment.

The reasoning behind a code fragment is the key to understanding it.

Okay, so commenting can be important. But then what should I comment? If you remember one thing from this article let it be to comment why rather than what. It's the biggest timesaver you can give to the future reader of a code fragment.

The reasoning behind a code fragment is the key to understanding it.

"My code is self-explanatory"

When you write code, you know why you write it. I call this the illusion of self-explanation. When you are writing code its meaning is indeed obvious to you because you have a whole context loaded in your head for this piece of code. Future readers often will not have this and need some help.

It is also the most heard argument against writing comments: the preference for writing self-explanatory code over code with comments. I believe they are separate things. Applying proper naming and code structuring is also required to keep code readable, but a lot of why (explanation) just does not fit in what (code).

Contagious Code and its Vaccine

Good programmers never reinvent the wheel. When programmers need a solution or implementation, they search Stackoverflow or more specifically: look in their own codebase if they solved the problem before already. If they did, they are happy to copy this proven solution instead of figuring out their own, and rightfully so. This is how certain code can 'reproduce' to new applications. I call this contagious code.

Contagious code is not a bad thing. I would argue that (if it can't be extracted) contagious code is a good thing as it provides consistency to the reader. However, there is a catch. If there is some dead code or technical debt hidden in that copied code, it is duplicated along. You want the same behavior, so you copy it. Now, of course, the copier could start pruning the copied code to find out if there are parts they do not need, but again this takes time. Time that can be reduced by explaining your code. Comments can avoid useless or even harmful code to be copied, i.e. to reproduce.

Let me illustrate this with another example, for those who are interested. This time on Kafka configuration:

kafka:

consumer:

max-attempts: 3

back-off-initial-interval: 70000

back-off-multiplier: 2

auto-offset-reset: latest

One day I stumbled onto this fragment in a recently created new microservice. For now, you don't need to understand the code's meaning, but in short: it configures a Kafka message consumer in a microservice. The last line, however, was clearly copied. It states that the first time the consumer starts, it should start at the last message, instead of the first. This line was purely here because one specific other microservice uses this. Several other microservices copied the full Kafka configuration from that one service, assuming it was what they needed since they wanted to use Kafka in the same way. Of course, this would not have happened if the creator of the new microservice had read every line they copied, critically. But this fragment is typically part of a 100+ config file that is copied as a sort of template. So what would be an easier way of avoiding malicious contagious code?

You probably guessed it. Add a comment to non-standard configuration like this. This will trigger the future copier to double-check if they need that line:

kafka:

consumer:

max-attempts: 3

back-off-initial-interval: 70000

back-off-multiplier: 2

auto-offset-reset: latest # Only required here because we want to skip old messages

Reveal Hidden Dependencies

One of the great features provided by decent IDEs is reference checking. Many times per day I want to know where a method is used and I can find out easily. But what if I want to know why certain application-level configuration was added? What code does it affect? Or why is a certain library included in this application? These implicit dependencies are often hard to track. Unless the writer makes them explicit by adding comments.

Time for another story, related to the same configuration code fragment:

kafka:

consumer:

max-attempts: 3

back-off-initial-interval: 70000

back-off-multiplier: 2

auto-offset-reset: latest

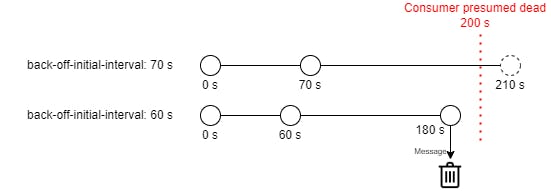

Simply put, this says: A Kafka consumer gets three attempts at processing a message. If the first attempt fails, try it again in 70 seconds. If that fails, try it one more time after another 140 seconds. Then give up and discard the message.

How was the value of 70 seconds chosen? It seems such an odd amount. It's not an even minute, nor a power of two.

Well, the inside knowledge you need to answer this question is that an external package configures the time a consumer gets for its three attempts combined: 200 seconds. What happens if I change the 70 to 60 seconds? The three attempts will be executed in roughly 180 seconds: before that timeout of 200 seconds. The message will be discarded by the consumer.

What happens then if the value remains 70 seconds? The 200 seconds consumer timeout ends before the third attempt is started (after 210 seconds). Kafka believes the consumer to be nonresponsive and the message is given to a different consumer before the message is discarded. The other consumer is allowed to start a new cycle of 3 attempts, and so on. This implies that the message will never be discarded. The application thus functions fundamentally different when changing the back-off-initial-interval value, but this is not self-explanatory! It does so in relation to the consumer timeout. Problems can be avoided by making these hidden connections between code visible using comments.

Beware of Comment-Code Duplications

Technical debt is always right around the corner, even when writing comments. Take a look at this made-up pseudocode fragment of a simple webshop:

function determineOrderOfItem(item) {

if (item.category === "General") {

item.order = 0;

}

...

}

If I read this code for the first time I ask myself: why is this logic necessary? Well, let's assume the writer of this code considered the possible confusion of future readers and added a comment to clarify this:

function determineOrderOfItem(item) {

// Our client wants items of the general category to be rendered first as they sell better.

if (item.category === "General") {

item.order = 0;

}

...

}

There. Now when a new developer comes along this code they understand the intent of the code. However, as time goes by, a second client comes along. This new client is a pet store and wants all items related to cats to be rendered first. The original writer knows what to do, and changes the code to accommodate this in a future-proof manner:

function determineOrderOfItem(item, priorityCategory) {

// Our client wants items of the general category to be rendered first as they sell better.

if (item.category === priorityCategory) {

item.order = 0;

}

...

}

That was not so hard either, but as you probably noticed they did not change the comment.

Again, a new developer comes by this code. They read the comment to understand it and run the code for the pet store. They notice that priorityCategory is "cat". Now the developer is asking themselves: Is this a bug? Should "general" be passed here, or is the commenting wrong? To find this out they will start analyzing the code history and unit tests and ask the business or the client to find out if the code is correct or not.

Now there are several ways this confusion could have been avoided, but I believe the root cause is the duplication of the magic string "general" in the comments. Even if developers remember to change the comments along with the code, the problem is they have to do two modifications: one in the code and one in the comments. Avoid time-consuming confusion and technical debt by not duplicating magic values into your comments.

Conclusion

Good programmers write good comments as well. Poorly commented code behaves as technical debt. Interest on it is paid every time a reader is confused about its meaning and has to spend more time on understanding it.

As programming consists primarily of reading, hours of time can be saved in the future by properly commenting your code in the present. Use these guidelines when thinking of comments to add:

- Comment why rather than what

- Add comments even when you think code is self-explanatory

- Point out non-standard parts in your code, to guide future readers to what is important

- Do not duplicate logic or magic values into comments

These tips are just the tip of the iceberg but I believe they will bring your commenting skills to the next level.

If you have more tips yourselves, please leave a comment!